Our team at WestEd, Formative Insights: Assessment for Learning, has been working with teachers in formative assessment to increase student agency for the last 10 years. Recently, we’ve had our ears to the ground to learn with and from teachers about how formative assessment and student agency translates to, and enhances, online learning. This post shares insights and ideas to cultivate collaborative classroom culture based on what we’ve learned from teachers using formative assessment practices.

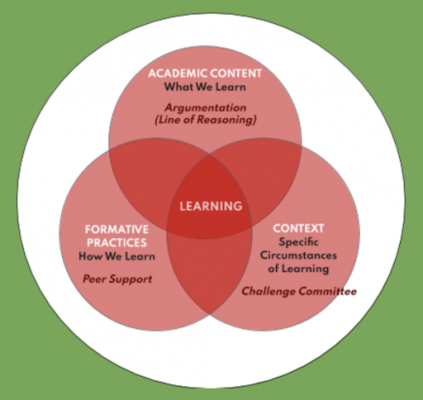

When Joe Nelson and James Ballew, high school English teachers in Tulsa, OK, thought about how to structure learning goals and experiences for their upcoming unit on argumentation in their Advanced Placement Language Arts course, they realized that they need to consider more than the disciplinary content and skills they want their students to learn. They also needed to identify the specific context for that learning (e.g., a particular book, play, or poem) as well and the formative processes students engage in to propel their own learning forward (e.g., reflecting on the status of their learning). This realization was in part a result of their thinking through how they would communicate to students, the what, why, and how of their learning. They also realized that their learning goals weren’t encompassing all that they were expecting students to learn – namely that the processes of “learning how to learn” needed to be explicitly taught and included in the goals for students. They communicated these three areas of focus to students as, What We Learn, Circumstances of Learning, and How We Learn.

Using this three-part model, Joe and James determined that in their upcoming unit, the disciplinary-specific skill of argumentation (oral and written) would be the “content” of the lesson. The “context” would be the novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, as a focus for developing arguments in a book banning, Challenge Committee debate. Joe and James also scaffolded this “context” by asking students to practice elements of argumentation in the realm of everyday current events in synchronous learning opportunities, which they were then able to connect to themes in The Handmaid’s Tale.

For the “formative process”, they chose peer support. This includes the practice of peers sharing their knowledge and skills with one another, providing feedback to support other’s learning, and then receiving both knowledge and feedback from others. In the video below, Joe explains this three part learning model to the students in one of his classes as part of a lesson on line of reasoning for argumentation. He also explains how this model relates to their learning in the current lesson. What is captured in this video is characteristic of the type of transparency that Joe and James provide for their students about the structures that underpin their learning processes. They do this in part because they want to build capacity in students to become co-constructors of their own learning by engaging in these structures themselves.

Now let’s take a closer look at each of these three components and how they show up in this unit, specifically in the lesson focused on line of reasoning.

Support for Learning Academic Content

Lesson part 1

Joe and James begin the lesson by explaining to their students that people can use several different types of reasoning in their arguments, with specific ones functioning better than others in different contexts. They explain that the reasoning structures function to:

- indicate chronology,

- describe events,

- clarify cause & effect,

- compare and contrast ideas,

- show problems & solutions, and

- articulate an order of importance.

The learning goal they set for their students related to this academic content is:

- Understand how and why authors use different lines of reasoning to strengthen an argument.

The success criteria for meeting this learning goal are:

- Describe the concept of a “line of reasoning.”

- Explain how a line of reasoning supports an argument’s overarching thesis.

- Use a line of reasoning to support a claim.

The role of formative assessment

The formative use of learning goals is important for student success in this lesson. They provide clarity for students on what they are expected to learn. They also provide “the why”, justifying for students the work they are being asked to do in the lessons – articulating the learning they should expect to get for their effort.

The success criteria, on the other hand, illuminate for students what they will be able to do when they have met the learning goal. The success criteria also help them to know how to demonstrate their learning, both to gauge the status of their learning for themselves and to share their learning status with others. For example, if a student found they had difficulty explaining to a peer how a line of reasoning supports an argument (success criteria #2), they would know that they hadn’t yet met the learning goal and could take action, i.e., select and utilize additional resources to accelerate their progress. Without the success criteria, students would have no way of knowing what to measure to gauge the status of their progress (i.e., their ability to describe, explain, and use a line of reasoning), nor would they know when they might need to take additional steps in order to meet the learning goal.

Lesson part 2

Next in the lesson, Joe and James model how to construct a line of reasoning appropriate for a specific context, describing how an author might need to describe, show cause and effect, or compare two ideas depending on their purpose. They then provide students with opportunities to practice, question, and reflect. To scaffold the use of the various lines of reasoning, they share transition words with students to use that support different reasoning structures. These words and structures include:

| Line of reasoning structures | Transition words and phrases |

| Chronology | after, since, while, next, finally |

| Description | to demonstrate, indeed, for instance, to illustrate, specifically |

| Cause & Effect | since, consequently, therefore, accordingly, however |

| Compare/Contrast | likewise, unlike, except for, on the other hand, alternatively, conversely |

| Problem & Solution | one problem is, the question is, if/then, the dilemma is, the solution is, so that |

| Order of Importance (Most to Least OR Least to Most) | additionally, first, another, primarily, least of all, most important, ultimately |

The role of formative assessment

Overall, the lesson is structured with the goal to support student capacity-building to independently use the target skills. The lesson generally follows the pattern of providing:

- Explicit instruction

- Modeling

- Rehearsal

- Practice

- Feedback

This process is not only used to support learning discipline-specific skills such as reading academic texts and constructing an argument, but also to support the skills students need to manage their own learning and develop student agency through formative assessment processes. While some students may have learned these skills through opportunities they’ve had outside of the school contexts, most have not. Explicitly teaching skills for “learning how to learn” is a key lever in creating more equitable access to disciplinary content and skills and opportunities for success.

These “learning how to learn” skills are formative assessment strategies which students use on a daily basis to take ownership over their own learning. The crux of these formative assessment processes is noticing, making sense of, and responding to evidence of learning. This means reflecting internally through metacognition, asking (in relation to the learning goal and success criteria), What do I understand? What do I still have questions about? What feels like a road block? and Where to next? Then reflecting externally on work-in-progress and through discourse with peers and teachers. Students also apply this lens to making sense of their peers’ work to support them in their learning. They ask peers questions, observe, and listen to gauge where peers are in their learning to be able to provide feedback.

The Context for Learning Disciplinary-Skills

Lesson part 3

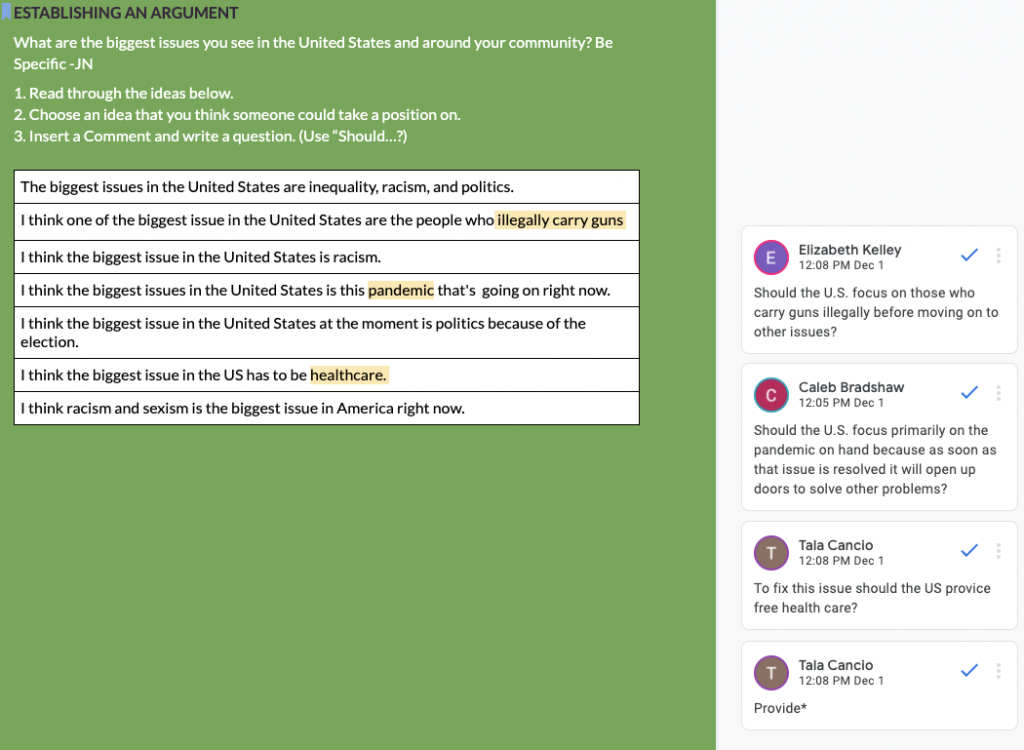

Before students dive into their independent learning activity during the lesson, Joe and James also go over the argument structure of thesis, claims, and evidence, sharing diagrams and giving examples. Throughout this lesson, students work specifically on creating claims. To check students’ level of understanding as they begin work on this topic (i.e., for the teacher to formatively gather evidence of learning) and to give them opportunities for low stakes practice (when students can also reflect on evidence of their own learning status and adjust their practice accordingly), the teachers provide students with a common context to think through the work and to practice their argumentation skills. The context they work in during this lesson is current events, specifically their own ideas about what they’ve identified as the biggest issue in the United States and in their communities.

Joe and James display this information in their module artifact during the lesson – a shared google doc that the teacher and students work in during lessons. In the current activity, students are asked to choose an idea from the list that they think someone could take a position on and then use the comment feature to ask a question related to this issue, starting with the word “should”. In the image below from the module artifact, the student-identified issues are on the left and the related, student questions are on the right.

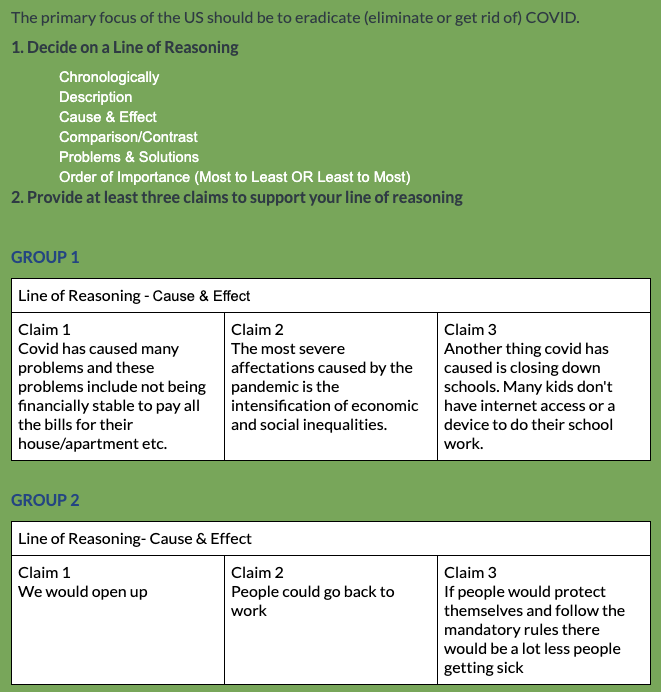

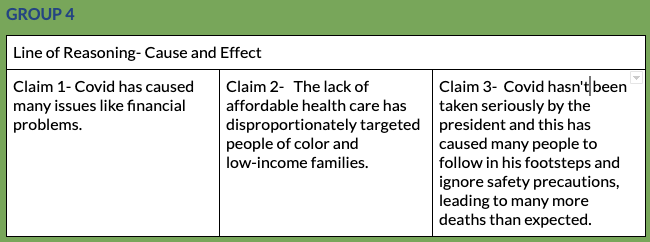

When students finish formulating their questions, Joe and James pick out one and turn it into a thesis statement for all the students to practice writing supportive claims. One of the students had asked, “Should the U.S. focus primarily on the pandemic on hand because as soon as that issue is resolved it will open up doors to solve other problems?” Joe turns this into the thesis statement, writing “The primary focus of the US should be to eradicate (eliminate or get rid of) COVID.” He then asks students to work in small groups to develop claims to support this idea. The image below shows the work of two of the four breakout groups who have chosen to use the line of reasoning, cause and effect, and have identified three claims to support the thesis. Through working in collaborative groups, students are able to learn from one another and collectively move towards the learning goal.

The role of formative assessment

Joe and James frequently use current events and other issues students care deeply about as the context for learning the target content during synchronous learning experiences. This dramatically increases engagement and investment in learning. It also provides a low stakes context for learning that is relevant for students and that most students are already familiar with.

When students are asked in a later interview, “What would you say that are things that happen in this class that help you stay engaged, that make you feel like you want to come back?” one student answered, “Well, I would say just… Like you said, just the discussions. Today, we’re about to discuss what happened at the Capitol. Last time we were discussing the presidential election. And then I think at one point we were discussing the Black Lives Matter protest. It’s just really interesting to see other people’s points of views of these events and what’s kind of happening and stuff.”

Another student followed up saying, “I would say that not only the topics, but also the teachers, because you can tell that they’re putting in effort and wanting you to learn and wanting you to understand. They ask if you’re understanding and how they can make it better, because they know it’s hard right now.”

This orientation towards providing structured opportunities to try out new skills in high interest contexts levels the playing field and provides for more equitable practice opportunities to increase target skills. With this structure, the context of the learning doesn’t get in the way of the content of the learning – both in terms of students being able to focus on the target learning and being able to accurately provide evidence of that learning. As discussed earlier, this is a key aspect of formative assessment – using evidence to inform decision making by both teachers and students.

In this instance, evidence that Joe and James gather about students’ ability to structure an argument during synchronous, online learning experiences is not conflated with issues that could arise if, for example, students were not as familiar or as confident in their ideas related to the context of learning. If they had started working right away during their online learning session with The Handmaid’s Tale and a student hadn’t read far enough in the novel to be able to participate fully, it would be hard for them to access the lesson content on argumentation or be successful meeting the learning goal even though neither are directly related to The Handmaid’s Tale.

By starting out with a common context in joint online work and then moving to the more specific context of the novel in asynchronous, independent work, students are better poised to succeed. This is especially true when they have opportunities for self-assessment and peer feedback during synchronous instruction which James and Joe often do using the comment markers in the module artifact.

Then when students approach their independent work, they have already developed the confidence and experience in writing claims successfully with fellow students in an area they are comfortable with and have strong opinions about. They also have had the opportunity to formatively self-reflect and make adjustments in how they proceed with their work. They can then independently repeat the process of writing claims using the context of The Handmaid’s Tale. With this structure, they can also read or reread the relevant section of the book before writing on their own time and are not on the spot in a synchronous learning experience.

Formative Practice – Learning How to Learn

The formative practice being developed in this lesson is peer support (feedback) – with students both sharing what they know with others and learning from others through reading and listening to their ideas and getting feedback on their own. Prior to this lesson, the teachers introduced unit learning goals and success criteria for formative practices. They are:

Learning goal

- Recognize the impact of peer support on learning.

Success criteria

- Explain how peer support affects your learning.

A primary way that Joe and James engage students in learning these skills is by making as much of the learning as public as possible. They ask students to verbally share their ideas, to put them in chat, and to write them in the shared module artifact (google doc). When students write their responses in the shared doc – usually by picking a row in a table and writing in their thoughts, they are also prompted to read what their peers have written. They often are prompted to respond and give feedback to their peers’ ideas by writing with comment markers or using different colored text in the same row. This is evident in the first example above, where students wrote their thoughts about major issues confronting the U.S. and then later went back and picked one idea as the source of an inquiry question that they posed.

When considering the public nature of learning through the module artifact, one student reflected that, “The module artifact I feel really helps me learn, because I can see what my peers think. And also, gives me another perspective of what answers are to my teachers questions and stuff. So I find them really helpful, personally.”

When students in this class were also asked, When you’re learning, what do you need to do to push your learning forward? What’s your responsibility?, they responded:

Student 1. I would say to help our peers in what they’re learning. And usually when you help somebody with their learning, you usually learn too.

Student 2. He [the teacher] also makes it to where we can sort of build on each other’s ideas. So we’re basically a big sort of family of ideas, and we can compress them into making them more compact.

Student 3. I’d say communication and participation.

Student 4. Yeah, I think that too. Really, without communication, you’re not going to get anywhere.

These students clearly express Lev Vygotsky’s notion that learning is a social process. The students value learning with and from their peers and feel a responsibility to support their peers’ learning with the belief that it also advances their own.

This disrupts traditional notions about success in school needing to be centered on individual ambition and competition. The students in James and Joe’s class demonstrate that the agency they feel is created in great part through the collective energy that comes from supporting and building off of one another’s learning. The pathway these students use to get there is formative assessment which enables them to use evidence to make substantive, informed decisions about their own learning. This in turn creates a more equitable classroom where all students have the tools to advocate for their own learning.